Berlin Elgar Hendrix

by Daryl Runswick[Home]

This is a piece about copyright.

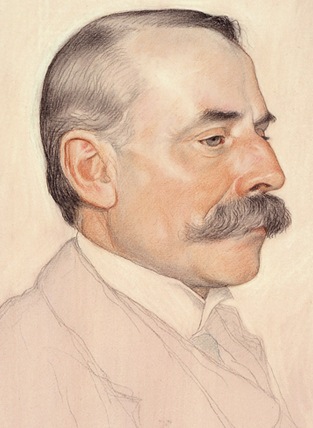

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

This is a piece about copyright.

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

left his Third Symphony incomplete. Preparatory

sketches for the work, in Elgar’s hand, were

reproduced posthumously in a book in 1936. In 1995

Elgar’s family commissioned the composer Anthony

Payne to complete the symphony, working up the

sketches into a finished piece, adding bridging

material of his own where necessary. Why? Elgar

had instructed that the sketches be destroyed. The

family, despite ignoring these wishes, had no wish

for the symphony to be completed. What made them

act? And why then, in 1995?

The answer lies in copyright law. Any work (musical or literary) remains the intellectual property of the heirs and/or publishers of an artist for 70 years after the artist’s death. During that period the copyright owners can licence or forbid the use of that work as they see fit. For 60 years the heirs of Sir Edward Elgar had forbidden any use of the sketches of the Third Symphony. But sometime in the 1990s they realised that the situation would soon change. At the end of the 70th-anniversary year of Elgar’s death, 2004, the Third Symphony would come into the public domain. Had the sketches been kept within the family, they could have simply hidden them from public view. But the pages had been published, and from 2005 would be available to any hack to do what he liked with. The solution of least harm, decided Elgar’s family, was to commission someone they trusted to complete the symphony: they could then control the quality of the result. In addition, the complete work would now remain under copyright protection for a long time into the future – until 70 years after Anthony Payne’s death, in fact: this is because any work of music or literature remains in copyright until 70 years after the death of the last surviving contributor to it.

I was personally affected by all this some years

ago: not in relation to Elgar or

I was personally affected by all this some years

ago: not in relation to Elgar or

his works, but to those of

Irving Berlin (1888-1989). I was commissioned by The King’s Singers

to arrange I’m Dreaming of a White Christmas for them, to

go on a CD called A Little Christmas Music. And I did, and

The King’s Singers recorded my arrangement, and it went, along with

two others I’d done, onto the CD. But then a snag arose. Irving

Berlin was still living, aged 100, still taking a lively personal

interest in his works. When the record company EMI wrote their usual

stock letter requesting permission to issue the recording, Berlin

demanded an enormous fee. EMI, astonished, had to decide what to do.

The CDs were already made, the booklets printed and boxed, the

cellophane wrappers were on. The decision they came to (The King’s

Singers told me) was to refuse to pay the fee and to trash the

entire print run of CDs. They then re-manufactured them with

White Christmas omitted: presumably that was the cheaper

option. I was disappointed of course, but they presented me with a

cassette of the recording

of my arrangement, so I could hear

how it went.

That was in 1989, and the sequel

is equally surprising. Berlin promptly died, that

same year. His heirs, not so fanatical in their stewardship of the

estate (which must already have run to billions)

issued a blanket permission for any Irving Berlin

tune to be recorded by anyone, for no fee (so long as the usual

royalties were paid on sales). And here’s the rub:

EMI’s CD had not yet come out. Did they now

reprint with White Christmas included again? Did they hell.

By the accident of a few weeks my arrangement

was consigned to history.

That was in 1989, and the sequel

is equally surprising. Berlin promptly died, that

same year. His heirs, not so fanatical in their stewardship of the

estate (which must already have run to billions)

issued a blanket permission for any Irving Berlin

tune to be recorded by anyone, for no fee (so long as the usual

royalties were paid on sales). And here’s the rub:

EMI’s CD had not yet come out. Did they now

reprint with White Christmas included again? Did they hell.

By the accident of a few weeks my arrangement

was consigned to history.

Or was it? I’ve been informed by Jo Fowler that

some people have copies of A Little Christmas Music with White Christmas present. My copy doesn’t, and

the track list on Amazon omits it. Curiouser and

curiouser.

Meanwhile, what do you think of this? – Irving Berlin’s first major hit tune, Alexander’s Ragtime Band, was composed in 1911 as the First World War loomed on the horizon. Because Berlin lived until 1989, this ancient melody by someone born in 1888 will still be in copyright until 2059.

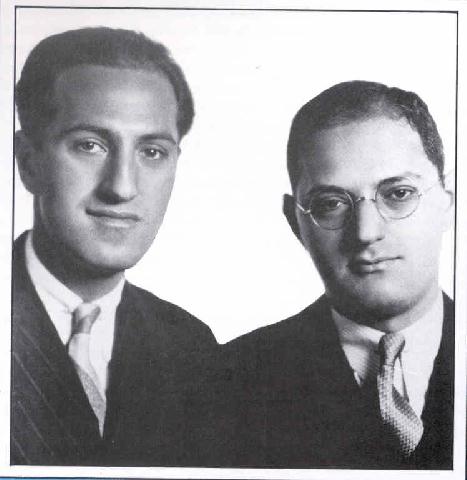

A similar situation holds for works by Gershwin, but not all of

them: George

died

in 1937, so Rhapsody in Blue came out of

copyright at the end of 2007.

in 1937, so Rhapsody in Blue came out of

copyright at the end of 2007.

But his lyricist brother Ira

didn’t die until 1983, so the song I Got Rhythm, composed

in 1930, stays in copyright until the 70th anniversary of Ira’s

death

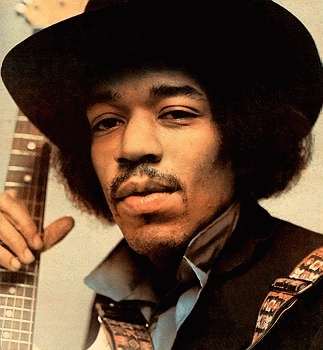

in 2053. Jimi Hendrix died young in 1970, so his

Purple Haze of 1966 will come into the public domain at

the end of 2040, nineteen years before

Alexander’s Ragtime Band – a song written half a century

earlier by a man 54 years Hendrix’s senior. A good pub quiz

question…

Footnote: my White Christmas arrangement also quotes

directly from Prokofiev’s Troika. Has EMI or anyone

else noticed? Prokofiev, and his publisher Boosey & Hawkes,

ought to be getting royalties too,

until 2023.